The Miami Marlins are sending RHP Edward Cabrera to the Chicago Cubs. In return, the Cubs are sending OF Owen Caissie (Cubs’ #1 prospect), SS/2B Cristian Hernandez (Cubs’ #11 prospect), and 18 year old 3B Edgardo De Leon to Miami.

The Chicago Cubs have officially made their first major splash in the offseason pond. While most of the offseason signings up to this point have been focused on shoring up a reworked bullpen, the Cubs have finally made the big-name addition to their rotation that many people were expecting. While much of the offseason scuttlebutt revolved around Tatsuya Imai (signed by the Astros), Dylan Cease (signed by the Blue Jays), Zac Gallen (unsigned), and Framber Valdez (unsigned), the front office has chosen to go in a different direction and acquire their starting pitcher via trade instead of free agency.

While I do think that the Cubs missed out on a quality arm in Imai, it’s clear that the latter free agent candidates were not as high on the Cubs’ radar as initially thought. Given the penny-pinching strategy of Cubs ownership, they were never going to be able to match the asking price of Dylan Cease. In Gallen, the Northsiders would have most likely had to pay around $20 million a year for a former Cy Young contender whose performance has regressed over the last couple of years. With Valdez comes a huge question mark around clubhouse chemistry given his much publicized incident with Astros catcher Cesar Salazar last season, and it’s my belief that the Cubs should steer far clear of the former Astro.

In shifting their focus to the trade market, the Cubs finally committed to a deal that has been theorized for a while. Prior to the 2025 trade deadline, the Cubs had been linked to Cabrera and his compatriot and rotationmate, Sandy Alcantara. At the time, the Cubs chose not to pursue a trade for either, as the asking price was deemed to be too steep by the Cubs’ front office. Rumors particularly swirled around some combination of Owen Caissie, Matt Shaw, and Cade Horton for one of the two Miami hurlers. While Caissie was still included in the final deal, it seems that Horton has been deemed untouchable and Shaw’s underwhelming season pushed the Marlins in a different direction; although it’s likely the Cubs preferred to keep Shaw as a utility option on the bench with the signing of Alex Bregman.

In analyzing this trade, we’ll take a look at each player and how they project to benefit their new teams. Let’s dive into the numbers down below.

Edward Cabrera

With Edward Cabrera being the main focal point of the trade as a whole (as well as being the only trade piece to have spent more than a full season in the MLB), we’ll focus on him, while also touching on the pieces of the trade that got sent to Miami. Cabrera, a 6’5 flamethrower from the Dominican Republic, has spent five seasons in the MLB while still only being 27 years old. In Cabrera, there is a lot to like. He throws hard, has a nice pitch mix, and he comes with three full years of club control. However, he has a tendency to walk batters and lose control of his pitches, he gets hit hard (and I mean HARD. 46.4 Hard-Hit %, 8th percentile), and he’s only thrown more than 100 innings once in his career (2025). Before we dive into the statistics, I’d like to take a look at his pitch mix because it can tell us a lot about his underlying performance and why the Cubs were willing to give up their #1 and #11 prospects.

Pitch Repertoire

As noted above, Cabrera has a great mix for an MLB starting pitcher. He throws a four-seam fastball and a sinker that average around 96 mph. He also offers a curveball and slider as breaking pitches, with the curveball playing far better against all hitters. Finally, his most freakish pitch is a changeup that he throws at an astonishing 94 mph on average. We’ll take a look at each pitch and it’s effectiveness against all batters below.

| Pitch | BA/xBA | SLG/xSLG | wOBA/xwOBA | Exit Velocity | Whiff% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-Seam | .267 / .298 | .583 / .661 | .417 / .451 | 94.0 mph | 18.1% |

| Sinker | .370 / .352 | .583 / .605 | .445 / .444 | 92.0 mph | 9.2% |

| Slider | .207 / .196 | .345 / .331 | .267 / .266 | 89.5 mph | 43.7% |

| Curveball | .142 / .126 | .245 / .204 | .223 / .203 | 87.1 mph | 45.2% |

| Changeup | .203 / .238 | .266 / .313 | .226 / .261 | 88.2 mph | 27.3% |

Cabrera’s curveball has become his best pitch, and there’s reason to believe that it’s even better than the actual statistics show (as evidenced by the expected statistics being lower than the actual statistics). Among qualified pitchers, Cabrera’s curveball had the best Curveball Run Value in all of baseball in 2025. The curve also had the 6th best SLG and wOBA, while having the 2nd best BA and Whiff% among all qualified pitchers. In essence, the pitch is disgustingly good and I don’t think Cabrera gets enough credit for developing the pitch into what it is today.

Cabrera’s second best pitch is his changeup, which has made headlines for how hard he throws it. The pitch was Top 15 in terms of Changeup Run Value among all qualified pitchers in 2025; 19th in BA, 5th in SLG, 9th in wOBA, and 11th in Strikeout%. While the pitch doesn’t drop as much as an average changeup, it does have 2 more inches of arm-side break compared to the average right-handed hurler. Combine this unique movement profile with the fact that the pitch is thrown as hard as an average MLB four-seam fastball, it’s easy to see why batters struggle against the pitch.

The third pitch that Cabrera has to offer is his slider. While not quite on the same level as the curveball or the changeup, the pitch is certainly effective. Although he didn’t throw enough sliders to be qualified, he is 13th in Whiff% among pitchers who threw at least 300 sliders in 2025. The metrics show that Cabrera’s slider isn’t a wipeout pitch, but it doesn’t need to be. As a third option, it does the job it needs to and Cabrera uses it effectively, particularly against right-handed hitters.

The issue with Cabrera last season was the fact that both his fastballs got hammered incredibly hard, particularly by left-handed hitting. In 2025, left-handed batters had a mind-boggling .933 SLG and a wOBA of .596 against his four-seamer, and posted a .565 SLG with a .434 wOBA against his sinker. Statistically speaking, the four-seamer was actually Cabrera’s best pitch against right-handed hitters last season, but he only threw 95 of them all season so the sample size is too small to conclude anything meaningful. His sinker on the other hand was still hit just as hard with a .641 SLG and a .465 wOBA. This general trend can be seen across Cabrera’s career, but it was especially glaring last season.

What could be the reason for Cabrera’s inflated fastball numbers? For one, his four-seamer runs incredibly straight. Compared to other right-handed pitchers, Cabrera induces 1 inch less of rise and over 3 more inches of tail or arm-side break. This leads to a pitch that’s easy to square up, even though it’s thrown hard. His sinker, while having 2 more inches of tail than MLB average, also has 2 less inches of drop. In other words, the sinker doesn’t necessarily sink. With a four-seamer that tails 11 inches, and a sinker that tails 17 inches, it leaves hitters a larger margin of error when trying to square up two pitches that are almost identical in speed.

Pitch Usage

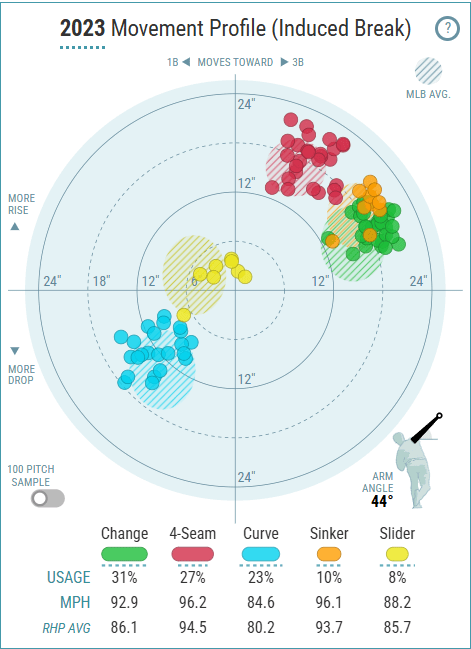

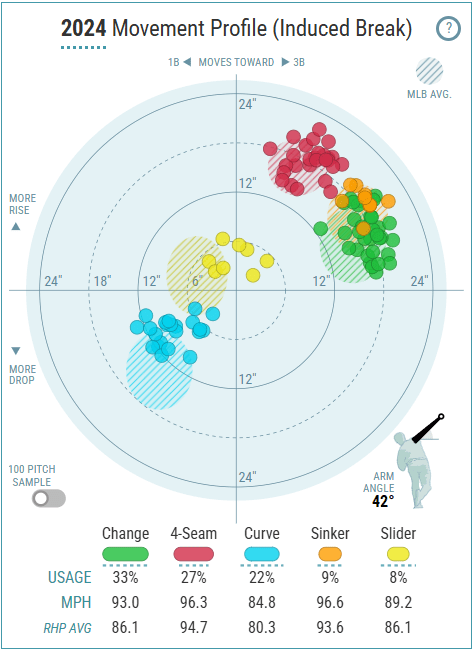

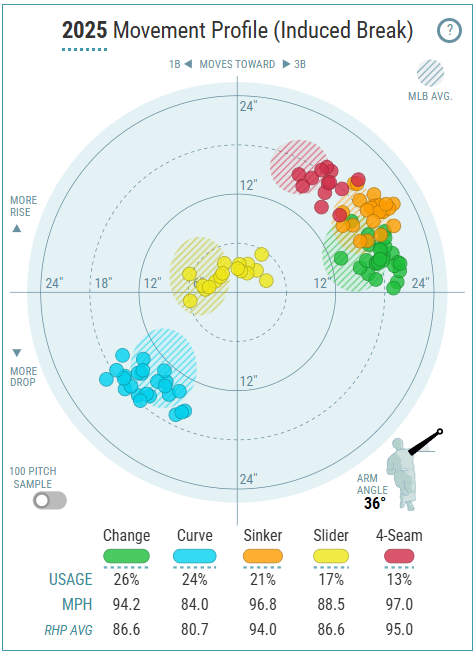

The graphics above were pulled from Baseball Savant and showcase Cabrera’s movement profile and pitch usage over the last three seasons.

In terms of general pitch usage, there are two important things to note in 2025 compared to his previous two seasons, which may give us some insight into why Cabrera had his most successful season last year. First, he relied on his changeup far less in 2025 compared to the previous two seasons (26% vs 31% and 33%). Second, he also dropped his fastball usage by over 10% compared to the previous two seasons (13% vs. 27%). While reducing the usage of these two pitches, he’s increased his variability by throwing his curveball (24%), sinker (21%), and slider (17%) more often.

This change in pitch usage has done two things for Cabrera. Firstly, it prevents hitters from sitting on his changeup, which is one of his best pitches. In previous years when he threw the changeup ⅓ of the time, hitters would see the pitch far more often which would give them an advantage as the game went on. Hitters also knew to sit on the pitch because he threw it so often. When the changeup often inevitably ended up as a ball because of its unique movement profile, it potentially contributed to his higher walk rates in 2023 and 2024. Secondly, by lowering his four-seam usage he was able to minimize the damage that was done to his least effective pitch. By utilizing the pitch less and relying more on his sinker (which has its own set of issues that the Cubs pitching coaches will look to rectify), he became a more effective pitcher.

One small change I would also like to note is the change to Cabrera’s arm angle. In 2023, Cabrera had an arm angle of 44 degrees, and it dropped slightly to 42 degrees in 2024. In 2025, his arm angle dropped down to 36 degrees. One wonders if this was an intentional change done by the Miami Marlins pitching staff to lessen Cabrera’s injury risk. A recent study from 2025 found that lower arm slots significantly reduce joint stress in the elbow and shoulder, without sacrificing velocity, which supports the findings of other recent research. This revelation is particularly important in Cabrera’s case because his injury history revolves around elbow sprains, tendinitis, and shoulder impingements; not severe UCL damage. Lowering Cabrera’s arm angle, in my opinion, is one of the reasons he was able to set a career high in innings pitched in 2025.

Platoon & Situational Usage

| Pitch | % against LHB | % against RHB |

|---|---|---|

| Four-Seam | 15.7% | 9.2% |

| Sinker | 11.9% | 24.1% |

| Changeup | 28.7% | 22.2% |

| Slider | 17.8% | 23.7% |

| Curveball | 25.9% | 20.9% |

Looking at the table above provides us with meaningful insights into how Cabrera tends to attack hitters on each side of the plate. First and foremost, we can see that Cabrera hesitates to throw his four-seam fastball regardless of the handedness of the batter; earlier in the article we touched on why.

Against left-handed hitters, Cabrera has two pitches that he relies on; throwing the changeup and curveball a combined 55% of the time. Since this is the more difficult matchup for a right-handed pitcher, it makes sense that he relies on his two best pitches more often than not. While throwing a slider that breaks in to a left-handed hitter isn’t my preferred method of attack, it again shows us Cabrera’s hesitancy to throw his fastballs in difficult matchups.

Besides the four-seam, Cabrera feels far more comfortable throwing all of his pitches against right-handed batters. This keeps hitters off balance because they can’t sit on a certain pitch. In particular, a sinker/slider combination seems to work well; the only problem is that RHB tee off on Cabrera’s sinker (.379 BA, .621 SLG, .453 wOBA). For this reason, I wonder why Cabrera doesn’t mix in his four-seam more often against right-handed hitters, if only to give them a different look.

I’ll also throw Cabrera’s pitch usage during 3-2 counts and 2 strike counts into a table below. I like to look at these particular situational counts because it can tell us what pitch a pitcher feels most comfortable with, and what he likes to use to attack hitters. I got this bit of information from watching an interview with Pete Rose, and if it’s good enough for Rose then it’s certainly good enough for me. While some may prefer to use 0-2 counts instead of the more general 2 strike counts, I prefer the larger sample size of 2 strike counts and find that the usage rates closely resemble each other anyways, particularly in Cabrera’s case.

| Pitch | 3-2 vs All | 3-2 vs LHB | 3-2 vs RHB | x-2 vs All | x-2 vs LHB | x-2 vs RHB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-Seam | 9.1% | 9.1% | 9.1% | 14.1% | 14.8% | 13.3% |

| Sinker | 17.4% | 16.9% | 18.2% | 7.4% | 8.2% | 6.5% |

| Slider | 19.0% | 16.9% | 22.7% | 16.2% | 11.6% | 21.4% |

| Curveball | 27.3% | 28.6% | 25.0% | 30.7% | 32.4% | 28.8% |

| Changeup | 27.3% | 28.6% | 25.0% | 31.6% | 33.0% | 30.1% |

The table above shows us what we’ve already concluded in this article; that Edward Cabrera’s best pitches are the changeup and the curveball and they’re also what he feels most comfortable throwing, regardless of the situation or the handedness of the batter. I’d also like to note that Cabrera tends to use his slider more often against right-handed hitters in 3-2 and 2 strike counts compared to his usage against left-handed hitters. Another thing that this table shows us is that in 3-2 counts, Cabrera tends to throw his sinker more often than his four-seam. In 2 strike counts, the inverse is true and he relies more on his four-seam fastball.

Now that we’ve taken a look at Edward Cabrera’s pitch repertoire and usage, I’d like to take a step back and look at his 2025 performance as a whole.

2025 Performance

When looking at seasonal performances, I like to compare players against their peers. This helps to account for slight changes in league-wide performance from year to year. For this reason, we’ll start with Baseball Savant’s Percentile Rankings for 2025. Looking at Cabrera’s below-average Run Value can be slightly misleading; his Breaking Run Value was 94th percentile and his Offspeed Run Value was 88th percentile, but his Fastball Run Value was in the bottom 5th percentile in the entire league. This supports our earlier conclusions that Cabrera truly needs to work on his fastball in order to flourish into a premier MLB starting pitcher.

One of the reasons the Chicago Cubs chose to trade for Cabrera is the fact that his Chase%, Whiff%, and K% are all Top 25% in the big leagues; he has bat missing stuff, which is something that the Cubs rotation lacks at the moment. While he is Top 25% in Ground Ball Percentage, he’s also bottom 8% in Hard-Hit%. Cabrera’s Walk% and Barrel% are also below league average. While he has the capacity to miss bats, he can lack control of his pitches at times and when hitters do make contact, it’s generally hard contact. I would like to note that Cabrera made big strides in reducing the amount of walks that he gave in 2025 compared to his previous seasons, but there is still some room for improvement.

Two particular statistics that worry me are Cabrera’s xERA (45th percentile) and xBA (52nd percentile). Cabrera’s 2025 ERA was 3.53 and his xERA was 4.04; telling us that he was getting lucky to some extent. Since xERA can be a decent predictor of future performance, this does raise some concerns in regard to his 2026 outlook. Since we’re looking at worrying trends, Cabrera’s Average Exit Velocity was in the bottom 22nd percentile of the league; yet again showing us that Cabrera tends to get hit hard when hitters are able to make contact.

While I’ve nitpicked Cabrera’s 2025 performance up to this point, he wasn’t nearly as bad as some of these numbers make him out to be. After all, he posted a 3.53 ERA, a 1.23 WHIP, and struck out 25.8% of batters; all great numbers. Even though he gets hit hard, this doesn’t lead to Cabrera giving up more home runs than the average MLB pitcher (1.11 HR/9). In general, he’s able to keep the ball in the park which bodes well for a good fielding team like the Cubs. One statistic that I particularly like is ERA-, which accounts for park and league adjustments and centers on a scale of 100; lower being better. Cabrera’s ERA- was 83, which shows that he’s able to limit the amount of runs that he gives up in a neutral environment.

Cabrera also performed well against both left-handed and right-handed hitters. He did tend to walk more left-handers than right-handers, and lefties also had a slightly higher SLG, but overall he was able to face hitters from both sides of the plate effectively. In particular, I’d like to note that Cabrera also performed better in high leverage situations than he did in low leverage situations or with the bases empty; I’ll showcase this in the table below. Please note that the sample size for high leverage situations is incredibly small (7 IP), but that the sample size for runners in scoring position is large enough to draw some meaningful conclusions from.

| Situation | AVG | OBP | SLG | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Leverage | .253 | .348 | .439 | .345 |

| Medium Leverage | .220 | .284 | .343 | .278 |

| High Leverage | .190 | .208 | .190 | .176 |

| Bases Empty | .230 | .318 | .375 | .308 |

| Men on Base | .238 | .294 | .381 | .295 |

| RISP | .228 | .285 | .366 | .283 |

As evidenced in the table above, we see a general trend that Edward Cabrera is better when the stakes are higher. This trend can be seen across most of Cabrera’s career, which supports my theory that he thrives when the stakes are higher. Notably, across Cabrera’s career, his batting average against is 40 points lower when runners are in scoring position compared to the bases being empty.

Overall, I believe that Edward Cabrera had a very solid performance in 2025. While he certainly has things to work on, his weaknesses aren’t a mystery. If the Cubs are able to help him with his fastball woes, I could certainly picture Cabrera becoming a Top 25 starting pitcher in the MLB.

2026 Outlook

In order to project Edward Cabrera’s 2025 performance, we’ll use a combination of expected statistics and a handful of projection systems like Steamer, THE BAT, MARCEL, and even a brand new projection system produced by FanGraph’s Jordan Rosenblum, OOPSY.

First and foremost, the difference between Cabrera’s ERA and xERA suggests that he overperformed in 2025 (3.53 vs 3.99), according to FanGraph’s numbers. However, Cabrera’s xERA was still under MLB average, which is a good sign for future performance. Cabrera’s xFIP was also slightly lower than his actual FIP, which suggests that he was getting slightly lucky with the amount of home runs he was giving up. I am of the belief that home runs are thrown instead of hit, and that pitchers are generally able to control the amount of home runs they give up; so I don’t put too much emphasis on xFIP, but it is certainly worth noting. In terms of BA and xBA, the numbers are fairly similar which suggests that Cabrera’s performance was pretty representative of his inherent ability. Overall, the expected numbers suggest a slight regression towards league average, but all signs point to Cabrera still being an above average pitcher in 2026.

Moving into projection systems, we’ll yet again use a table to make sense of a few different projection algorithms and how they predict Edward Cabrera’s 2026 performance.

| System | IP | BA | WHIP | ERA | K-BB% | FIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steamer | 140 | .236 | 1.30 | 3.97 | 15.5% | 3.92 |

| THE BAT | 142 | .224 | 1.23 | 4.00 | 15.3% | 3.95 |

| MARCEL | 138 | .236 | 1.24 | 4.04 | 14.6% | 4.27 |

| OOPSY | 142 | .221 | 1.26 | 3.54 | 16.2% | 3.77 |

| Average | 140.5 | .229 | 1.26 | 3.89 | 15.4% | 3.98 |

In the table above we take a few projected statistics from a handful of different projection systems. I decided to include the new OOPSY projection system because of it’s incorporation of Stuff+, as well as a few other inclusions; you can read more about OOPSY here. When using projection systems, my preference is to average them out. No one projection system is ever going to be completely accurate. No one projection system will ever be the best system 100% of the time. For this reason, I choose to look at the average of the four systems I decided to include in this article.

There are a few main takeaways here. For one, Cabrera is unanimously projected to surpass his career high in innings pitched, indicating that he should hopefully be able to remain healthy next season. Secondly, when averaging all four systems, Cabrera is projected to be better than the 2025 league average in all listed statistics. This, yet again, lends me to believe that while we may be likely to see a regression towards the mean in 2026, Cabrera’s performance will still be above average for a major league starting pitcher.

One last addition that I would like to talk about is K-BB%. This particular statistic can do two things for us. Firstly, I’ve found a strong positive correlation in K-BB% and yearly pitcher performance (Tarik Skubal, Garrett Crochet, Paul Skenes, Joe Ryan, and Ryan Woo led the majors last season in that order). Secondly, and more importantly, K-BB% can also be a great predictor of future performances (often outperforming many expected statistics like xERA and xFIP). In 2025, Edward Cabrera had a career high 17.6 K-BB%, which would be good for 29th among pitchers with more than 100 IP last season. The fact that he’s around the Top 25% in baseball, and that he set a career high, tells me that Cabrera is primed for a solid 2026 season; but only time will tell.

Owen Caissie

Owen Caissie was drafted by the San Diego Padres in the 2nd round of the 2020 MLB Draft. The 23 year-old Ontario native was acquired by the Cubs later that year in a deal that sent Yu Darvish and Victor Caratini to San Diego. Caissie, listed at 6’3 190 pounds, made his MLB debut in 2025; playing in 12 games and receiving less than 30 plate appearances. For this reason, his .192/.222/.346 slash line is incredibly misleading, so we’ll be focusing on his career in the minor leagues and how he projects to fit into the Miami Marlins lineup.

While in the Cubs’ farm system, Caissie was aggressively promoted and reached AAA Iowa by the time he was 21 years old. His bat speed and raw power carried him throughout the minors, and he slugged 41 home runs across two seasons in AAA. Batting from the left side of the plate, Caissie is able to leverage his big frame to produce power that plays to all parts of the field. In 2025 AAA, he posted a wRC+ of 139; an incredible number for a 22 year old with limited experience. He also had a HardHit% of 52.6% at AAA last season, which would place him among the likes of Yordan Alvarez, Ronald Acuna Jr., and Yandy Diaz if he’s able to replicate that kind of power in the Majors.

He also has plus speed for a corner outfield position and has incredible arm strength to play RF in the majors. His fielding ability could certainly use some work, particularly regarding his reads and routes to fly balls (which he has improved upon since entering professional baseball). The problem with Caissie is that he has a 30% strikeout rate across all his seasons in pro ball. While I won’t focus on his limited sample size in the big leagues, he struck out over 40% of the time when he got called up last season. He’s able to slightly offset the negative impact of the strikeouts by walking around 13% of the time at AAA, but he’s going to need to cut down on the swing-and-miss if he wants to succeed at the big league level.

With Caissie, there’s plenty of reasons to be excited; after all, he was the Cubs #1 prospect for a reason. From the Cubs perspective, he was supposed to be the in-house replacement for Kyle Tucker. While there’s no way that a player of his age can live up to those lofty expectations, he has an incredibly high ceiling for such a young hitter. The Cubs had a logjam in the outfield with Ian Happ, Pete Crow-Armstrong, and Seiya Suzuki locked in as starters and Kevin Alcantara knocking on the door (with Ethan Conrad potentially playing a role down the line). The Cubs decided that Caissie’s best use was as a trade chip to bolster the starting rotation.

From Miami’s perspective, it’s easy to see why the Marlins wanted to acquire him. An outfield consisting of Josh Stowers, Jakob Marsee, and Owen Caissie is incredibly intriguing and I’m excited to watch that potential combination for years to come. Even if Caissie takes a few years to blossom, the Marlins are in no position to win now and they have the ability to let the young outfield prospect adjust to MLB pitching (something that the win-now Cubs do not have the luxury of affording).

Cristian Hernandez

Cristian Hernandez is an intriguing prospect to look at, particularly considering he debuted in Low A ball when he was only 19 years old. Signed by the Cubs in 2021 out of the Dominican Republic for $3 million, Hernandez drew comparisons to Alex Rodriguez and Manny Machado as a teenager. He was an incredibly well rounded athlete that graded as an above average contact hitter with well above average fielding potential and speed as a teenager.

However, Hernandez’s development hasn’t come as quickly as he nor the Cubs would have liked. In 2024, he was able to get his feet under him at Low A and posted a .269/.382/.406 slash line with a wRC+ of 139. However, after earning a late-season promotion to High A, he wasn’t able to carry that momentum with him and struggled the rest of the season. Spending all of 2025 at High A, he performed as an average hitter, posting a 99 wRC+. At 22, it is almost certain he’ll start the 2026 season back at High A with the Miami Marlins, although he may end up starting the season in AA depending on how the the front office views him.

Hernandez has great bat speed and is continuing to fill out his athletic 6’2 frame, it just hasn’t translated into results yet (.113 ISO and .365 SLG in 2025). He has evolved as a hitter and chases less than he did when he broke into pro ball, while also learning to use more of the field to his advantage. In particular, Hernandez struggles against quality fastballs; something that doesn’t bode well for life in the big leagues. In the fielding department, he has range and athleticism to play shortstop, but his arm is the question. He’s prone to throwing errors and certainly needs to refine his accuracy if he wants to move through the farm system and break into the big leagues.

From the Cubs perspective, trading Hernandez was an easy move. They already have Dansby Swanson and Nico Hoerner up the middle (even though Hernandez is unlikely to debut until 2027 at the earliest). They also have Matt Shaw, who has the potential to play across the infield, and they have Jefferson Rojas and James Triantos down on the farm that are expected to be ready for the MLB within the next couple of years. With Hernandez’s development slowing, it’s easy to see why they were willing to include him in this package.

For the Marlins, I’m not exactly sure how Hernandez fits into their vision. They already have Aiva Arquette, Starlyn Caba, and a handful of others that have the potential to break into the majors at the middle infield positions by 2028. From what I can tell, none of these players have have blown away the Marlins’ front office with their development. This may be what enticed the Marlins to consider adding Hernandez; another player to take a chance on and hope that one or two of them works out within the next few years.

Edgardo De Leon

De Leon is a difficult prospect to profile for many reasons. For one, the 18 year-old Dominican has played less than 100 games between the Dominican Summer League and Complex League. Granted, he did post a wRC+ of 142 and walked almost as often as he struck out as a 17 year-old in the DSL, and was above average when he made the move to the Complex League. However, being a good hitter at these levels is far from a guarantee that he’ll be able to replicate that kind of production as he moves through the levels of professional baseball.

Still, there’s reason to be excited about De Leon. In the 2025 Complex League, he had a 48% hard hit rate and a 107.6 EV90. Although, the amount of effort that it takes him to swing that hard is going to require some mechanical refinement as he develops and faces tougher pitching. This is evidenced by his contact rate of 66%, which isn’t great particularly for someone at his level.

Most of his pro ball experience has come at the corner infield spots, but he’s also spent some time in the corner outfield spots as well. Listed at 6’0 170 pounds, De Leon has an athletic build that supplies ample power to his bat. With a prospect this inexperienced, it’s nearly impossible to predict how his career will play out. That being said, I can understand why the Marlins wanted to include him in this trade deal. Whether or not he pans out is of little significance to either team, as of right now.

Conclusion

In a trade that sees the Chicago Cubs sending their #1 and #11 prospects to the Miami Marlins in return for Edward Cabrera, both clubs seem to come out winners. The Chicago Cubs get a solid starting pitcher for their rotation which offers them flexibility for the 2026 season and beyond without breaking the bank. In return, the Miami Marlins get a power-hitting outfielder to add to their Opening Day roster, a middle infield prospect that shows flashes of promise, and an 18 year-old fringe prospect.

For the Chicago Cubs they gain a lot of flexibility in their rotation. On Opening Day, the rotation should consist of Shota Imanaga, Matthew Boyd, Edward Cabrera, Jameson Taillon, and Cade Horton. As fringe starters, potential bullpen additions, or injury insurance, they also have Colin Rea, Javier Assad, Ben Brown, and Jordan Wicks. The impending return of Justin Steele at some point in the season is also worth keeping an eye on; who will get bumped from the rotation if everyone is healthy?

For the Miami Marlins, Owen Caissie offers a lot of upside. He boasts some of the best bat speed in the farm system and is able to hit with power to all parts of the field. While his strikeout numbers are concerning, Miami is in a position to allow Caissie to adjust at his own pace without worrying about joining a win-now roster with eyes on the postseason. Whether he can lower his strikeout numbers is to be determined, but his power and arm strength are enticing enough to prompt the Marlins to be patient with the 23 year old.

While Cristian Hernandez has a long ways to go before he ever puts on a major league uniform, he has the potential to get there. How long will that take? That’s the major question for a young prospect who had a lot of hype when he signed out of the Dominican Republic as a 17 year-old. His development hasn’t come along as rapidly as most would like, but the potential is still there. In the same vein, but requiring much more patience, is the 18 year-old Edgardo De Leon, who has yet to graduate past rookie ball. Yet again, the potential is there, but he is far too young and inexperienced to draw any definitive conclusions.

All statistics and metrics were pulled from FanGraphs, Baseball Reference, and Baseball Savant unless otherwise noted

Leave a comment